Religion affected almost every aspect of the way people lived in the Middle Ages. The Church taught that there was only one true religion, Christianity, and only one way to follow it - through the Catholic Church. The medieval church taught that those who did not follow church teaching would burn in hell in the next life. For this reason, the Church's attitude to people with different views was very harsh. Christian scholars were persecuted when they disagreed with official teaching; heretics were burned at the stake. Campaigns and crusades were launched to drive infidels from Jerusalem and the surrounding areas.

Throughout the Middle Ages a succession of popes outlined the powers and responsibilities they believed they held under their papal authority, including political power. As the head of the Church, the pope was very important. On this, everyone agreed; but some scholars went further than this. They argued that the Pope should even tell kings and princes what to do. The European kings, whether from true religious fervor, an astute recognition of the advisability of staying in the good graces of the Pope, or the need for religious sanctions to their warring nature, funded and participated in campaigns to the Holy Lands. They did not go unrewarded. Desire for land, desire for gold and a postponement of debt until a crusader returned, along with the honor and glory of having fought for Christ were all benefits gleaned from participating in the crusades.

In turn, during times of upheaval in their homelands, an appeal to the Pope was often used as a method to buy time to regroup finances and armies, or simply as a last resort. One of the most widely known is the appeal to Pope John XXII in 1320, known as the Declaration of Arbroath, assumed to have been composed by Bernard de Linton, Abbot of Arbroath and Chancellor of Scotland. The Pope had not previously accepted Scottish independence, perhaps because of Edward I's obvious and generous devotion to the Church, coupled with the fact that Robert the Bruce had been excommunicated for killing John Comyn in a church in Dumfries in 1306.

Within their homelands, kings relied on bishops to assist in the governing of the country. They were often appointed to look after the kingdom during the absence of the King. Bishops were involved in castle building, warfare, acted as ambassadors to foreign countries, financial advisors; all the while carrying out their priestly duties of overseeing every aspect of Church life in their diocese, or territorial unit into which the Church was divided. These duties included giving advice to the clergy and making sure they were leading their lives accordingly, visiting the church buildings to see that they were kept in a good state of repair, confirming young children in their faith and training and ordaining priests.

The chief church of the diocese was the cathedral. This was the Bishop's church and here he led the people in saying Mass and worshiping God. Bishops were called on to perform all of these tasks because they were the most highly educated men of the time. The King needed officials who could read and write, and it was difficult to find such men outside the Church. Thus, the bishops, more so than the pope, were caught up in the everyday political life of the country from which they served.

Frequently the bishops found themselves in an awkward position. They served the King, but they owed obedience to the Pope. In England in the twelfth century the issue ended in bloodshed. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, and the King, Henry II, took opposing views about where the bishops' loyalty should lie. "The clergy have Christ alone as King," Becket was purported to have said. Legend has Henry demanding reply as, "Who will rid me of this turbulent priest?" Four knights overheard him and, thinking that they would earn the King's gratitude, murdered Becket. Becket was made a saint, and pilgrims flocked to worship at his shrine.

A religious life was highly thought of, but none more so than the monastic way of life. Monastic life was highly organized and regimental. The daily timetable used in many monasteries and convents dated back to the the rule of St. Benedict in the late fifth century. This 'rule' of life was soon used by monks all over Europe. The monks who followed it became known as members of the Benedictine Order. There was also a similar order created for Benedictine nuns, started by St. Benedict's sister, St. Scholastica.

The Benedictine Rule gave a pattern to each day. Prayer, manual work in the fields to produce food for the monastery, work in the cloister (a covered walk around four sides of a square at the heart of the monastery) used for studying, writing prayers and producing books filled the monks' hours. Nuns did not study but spent time in cloister sewing clothes for the poor or preparing medicines. When people became monks or nuns, they made three vows. They swore to give up all their personal possessions (the vow of poverty), they promised not to marry (the vow of chastity) and they promised to obey the head of the monastery or abbey, the abbot or abbess (the vow of obedience).

As time went by, the Benedictines were criticized for a number of reasons. Some monasteries had become wealthy, some monks failed to keep their vows. New orders of monks were founded by enthusiasts who wanted to change these things. One new order was the Cistercian Order. The order became respected at once. Those lacking the ability to learn all the Latin prayers for the services could still have a place with the Cistercians. They became lay brothers, or conversi. Lay brothers helped work on the monastery estates and joined in what services they could in church. Over seven hundred Cistercian houses were founded in Europe.

Not all people felt they could endure the discipline of monastic life. People who wanted to show how much they respected this way of life, but who did not want to take religious vows themselves gave gifts to the monasteries or convents. Nobles gave lands for the building of new religious houses in exchange for prayers. Others gave gifts of gold. Such gifts brought problems for the monks and nuns. They were difficult to refuse and in time there were monasteries that became wealthy as a result.

The monks found that they were not as cut off from society as they had intended. They had extensive estates to run and workers to supervise. It was not long before the Cistercians and the other new orders were criticized as much as the Benedictines. Throughout Europe dissatisfaction spread, which lead to reforms in the Church known as the Protestant Reformation, and essentially the end of the Middle Ages or medieval era.

Cathedrals, as well as many abbey churches and basilicas, have certain complex structural forms that are found less often in parish churches. Read more at Wikipedia.

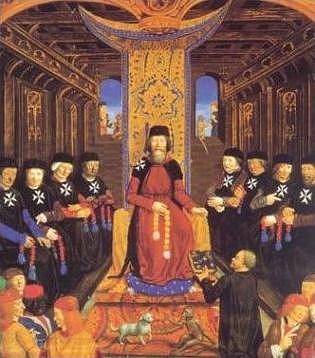

The Hospitallers arose in the early 11th century, at the time of the great monastic reformation, as a group of individuals associated with an Amalfitan hospital in the Muristan district of Jerusalem, dedicated to John the Baptist and founded around 1023 by Gerard Thom to provide care for sick, poor or injured pilgrims coming to the Holy Land. ... Read more at Wikipedia.